These two related concepts are fundamentally different, and complementary. I use them in my work in cybersecurity, but the current crisis better illustrates the point for the general public.

How can we mitigate the damages from the next pandemic?

This is a risk question, one that is typically studied by the likes of WHO and re-insurers. It requires the estimation of future probability and the likelihood that it will spread up to a point where it will damage the emergency response. A risk assessment results in recommendations to mitigate these potential impacts (whether they are followed is another story, because resource allocation is hard in the face of rare and extreme events).

The main use of risk, as an assessment, is therefore to help rank policies either in time or resource cost. It’s important to understand that there is no standard measure of any of probability or likelihood, so it’s only possible to compare your own estimates, not with others, except in very specific cases (the most prominent of which are financial markets, designed around the concept of “risk neutral measures”). This view goes against popular but meaningless popular wisdom, that risk is “the effect of uncertainty on objectives” (which is NIST definition of cyber risk). It’s not uncertainty that affects objectives but incidents whose occurrences are uncertain.

What do we do when we have a pandemic?

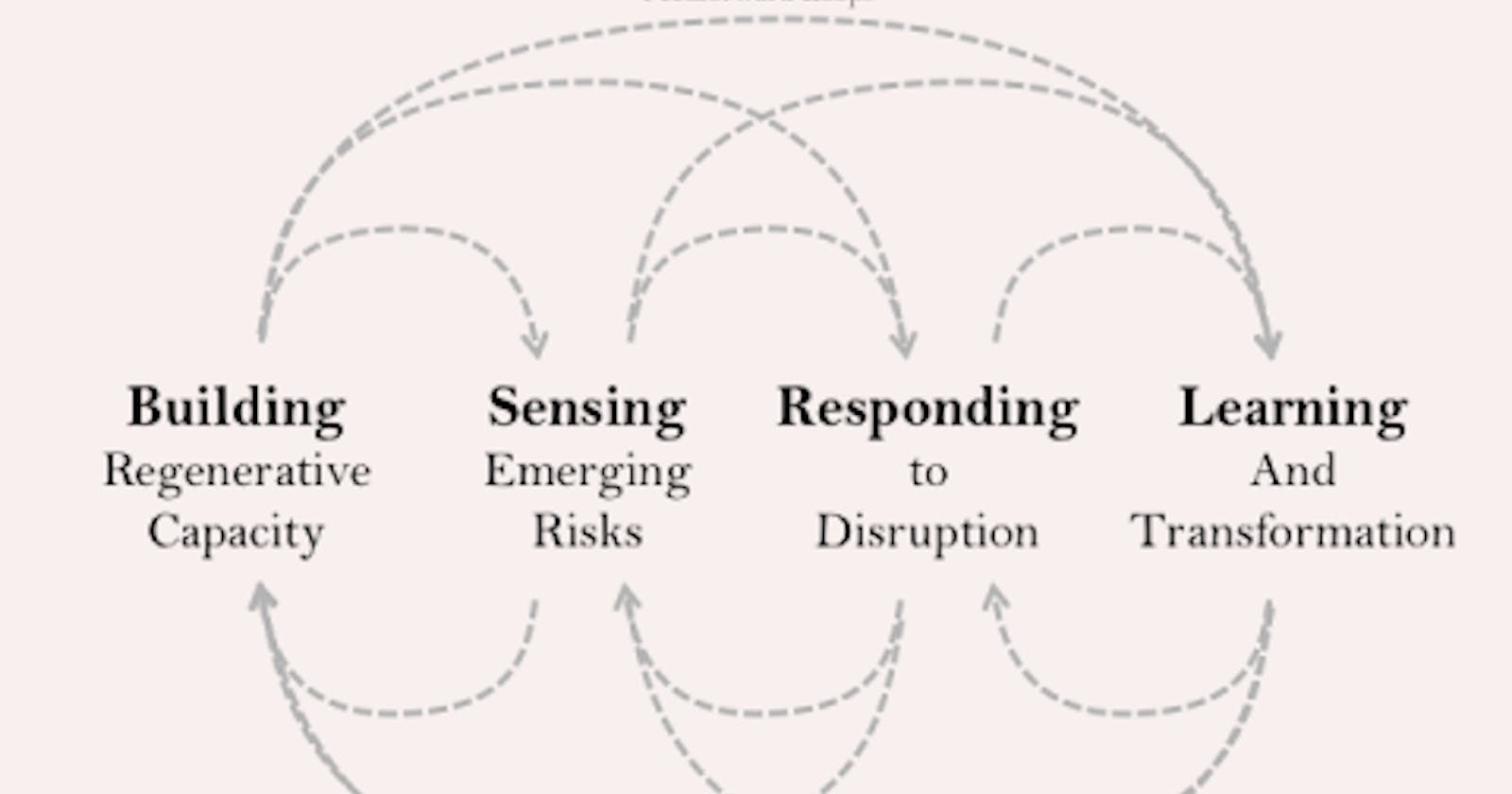

This is a resilience question, one that is typically dealt with by emergency responders (but we are now all facing it). The answer focuses attention on understanding how pandemics are sensed, anticipated, responded to, and learned from. The objective is to enhance these actions during disasters, knowing that you act in a complex and conflicted world (for instance having to deal both with sanitary and economic impacts), well beyond your comfort zone. It may seem counter intuitive, but real experts, despite being the most prepared, don’t say: “recent events have proven that I was right all along”, instead they actively build/sense/respond/learn to make sense of what is really going on and deal with the situation.

](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/2000/1*QX-6gpwbIDDppjUlUi6brw.png) Source : http://andrewzolli.com/the-verbs-of-resilience/

Source : http://andrewzolli.com/the-verbs-of-resilience/

Pr. David Woods, a famous scholar in the field, has made a great summary of what that means for covid19, in 10 points, which I reproduce here to illustrate (in a form I edited to keep it concise, but you can read the full papers).

What Matters When We are in the Middle of Evolving Covid-19 Pandemic? (David Woods)

The pandemic consists of a rolling series of outbreaks across the world which provides opportunities to anticipate, learn, adapt, and build capabilities for areas later in the series. Learning, adapting and acting effectively leads to reduction in excessive deaths. All have roles to play to accomplish this.

Keeping pace at scale: its all about matching two rates: challenge (get transmission rate below 1) and response (capacity to deal with hospitalization)

When mismatched, outcomes are worse — excessive deaths = ratio of fatalities experienced in a given jurisdiction relative to the best performing jurisdictions. Doing well at matching the two rates reduces excessive deaths. How much? This is hard to know when you are in the middle of the crisis. My estimates are 4x to over 10x. This drive the moral issues (#9).

Anticipation paradox: effective counter measures require action in advance of the direct experience of tangible harm, but the ability to engage/mobilize/generate the response mechanisms can be limited without tangible harm.

Approaching overload: anticipating how medical systems can be overwhelmed and act to generate and mobilize new forms of deployable capabilities. Failure to do so increases excessive deaths ratios.

New forms of coordination at new scales are required to respond effectively.

The global scale of the Covid-19 challenges have shocked the as-is system. The scale of the challenge reveals how the obsessive pursuit of optimality has undermined sources of resilient performance resulting in severely brittle societies.

Solidarity. Every one is on the scene of the crisis and therefore at risk. Every one is an actor in the evolving outbreaks. Every ones’ actions affect the ability to minimize excessive deaths. Promoting social solidarity to pull together is part of responding to the challenge over time event, though the significant time delays in the disease processes make this difficult. Efforts to synergize social solidarity goes well beyond epidemiological simulations that project the scale of infections, overload, and fatalities.

Can you do some thing to make difference? Where making a difference means reducing excessive deaths and supporting the people near or on the front lines who care for the sickest victims. If you can, then there is moral imperative to act to make that difference.

What allows societies to move or bounce forward as the pandemic resolves? We [Tom Seager, Dave Alderson and David Woods] are proposing four criteria for societies to relax restrictions (each of these need to operate at very large scale).

Criteria 1: do you have the testing infrastructure to test/track/isolate as new cases emerge that could become new hotspots?

Criteria 2: do you have he ability to ramp up care capacity to provide treatments for all who become seriously ill, while still providing care for others?

Criteria 3: can you provide safe and effective treatments to promote recovery for patients seriously ill from Covid-19?

Criteria 4: have you created the ability to build immunity and assess immunity in the population through antibody testing and vaccines?