Most digital privacy advocates take user consent as the go to solution to avoid Big Brother. But does that stand the test of reality?

Online consent is not a trivial process. source: BBC

Online consent is not a trivial process. source: BBC

This discussion stems from a thought provoking tweet, to say the least. “Maybe consent should have no place in privacy law”.

Which makes it a great starting point to reflect a bit on our digital habits.

More than 50 years ago already, U.S. Justice Michael Musmanno, eloquently expounded on the importance of that right:

The greatest joy that can be experienced by mortal man is to feel himself master of his fate, — this in small as well as in big things. Of all the precious privileges and prerogatives in the crown of happiness which every American citizen has the right to wear, none shines with greater luster and imparts more innate satisfaction and soulful contentment to the wearer than the golden, diamond-studded right to be let alone. Everything else in comparison is dross and sawdust. — Commonwealth v. John Murray, 223 A.2d 102, 109 (Pa. 1966)

In the context of digital applications, privacy regulations appeared very recently. EU’s GPDR (General Data Protection Regulation) started in 2018.

Personal information may relate to many types of data:

provides a data privacy vocabulary ontology](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/2668/1*jweB7oO-XY59eeSgC2KXQw.jpeg) The W3C DPV provides a data privacy vocabulary ontology

The W3C DPV provides a data privacy vocabulary ontology

Contrary to popular belief, GDPR does not necessarily require businesses to obtain consent from people before using their personal information for business and data processing purposes. Rather, consent is just one of the other five legal bases outlined in Article 6:

Processing is necessary to satisfy a contract to which the data subject is a party (for instance, I need to deliver your purchase at your home address)

You need to process the data to comply with a legal obligation (for instance, apply tax codes based on your location)

You need to process the data to save somebody’s life (for instance, this has been discussed in relation to covid tracking apps)

Processing is necessary to perform a task in the public interest or to carry out some official function (for instance, computing statistics related to the pandemic)

You have a legitimate interest to process someone’s personal data. This is the most flexible lawful basis, obviously.

This opens the door to interpretation, and there comes the almighty privacy policy. I mean, better safe than sorry, even if though consent remains a “fragile” legal basis because of the regime “easy obtained-easy revoked”. According to the GDPR, privacy policies should be delivered in a “concise, transparent and intelligible form, using clear and plain language”. But based on a review of 150 of those policies, “these are documents created by lawyers, for lawyers. They were never created as a consumer tool.” (source : NY times).

Consent is hard to do right

Each policy takes an “average of 10 minutes to read, an average individual encounters around 1500 of those each year. 76 work days!” (source: TheAtlantic). Consumers obviously don’t read, understand or acknowledge any of those terms (and even if they did once, the providers change them regularly). And that study was conducted in 2012, before data brokers were so prevalent. Without tools such as Scripta Manens, it would be impossible to decypher, to such a point that some artists denounced that situation visually:

Reading terms and conditions, by designer Dima Yarovinsky

Reading terms and conditions, by designer Dima Yarovinsky

We can do better to make consent more human friendly. CMU’s CyLab has tested many usability options to better inform consumers on privacy and security. They found that privacy options often remain hard to find. On March, 2021, California recommended adoption of a blue stylized toggle icon, which might serve as a starting point:

](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/2000/1*-oopGfQaGnAZuXyoE6VIOQ.png) CCPA approved “Privacy Options” button (but the state opt-in/opt-out remains hard to guess from the flat icon, it would be good that designers further help on this). Source: cylab

CCPA approved “Privacy Options” button (but the state opt-in/opt-out remains hard to guess from the flat icon, it would be good that designers further help on this). Source: cylab

New forms of user analytics (such as plausible or offen) focus on opt-in and opt-out mechanisms, as a technical solution. Application services can rely on authorization frameworks such as OAuth2 to include the resource owner’s consent, and the newer IETF GNAP (of which I am co-editor) strengthens privacy in the core protocol design. Other initiatives, such as Berners-Lee’s solid, try to implement personal data spaces.

Consent is no panacea

Despite all that technological goodwill, the practice of privacy notices often remains misleading, and sometimes harmful. Trust is coercive to the individual in the sense that a shrink-wrap license, or being forced to sign a privacy notice before getting care at a hospital is coercive to the sick and anxious person.

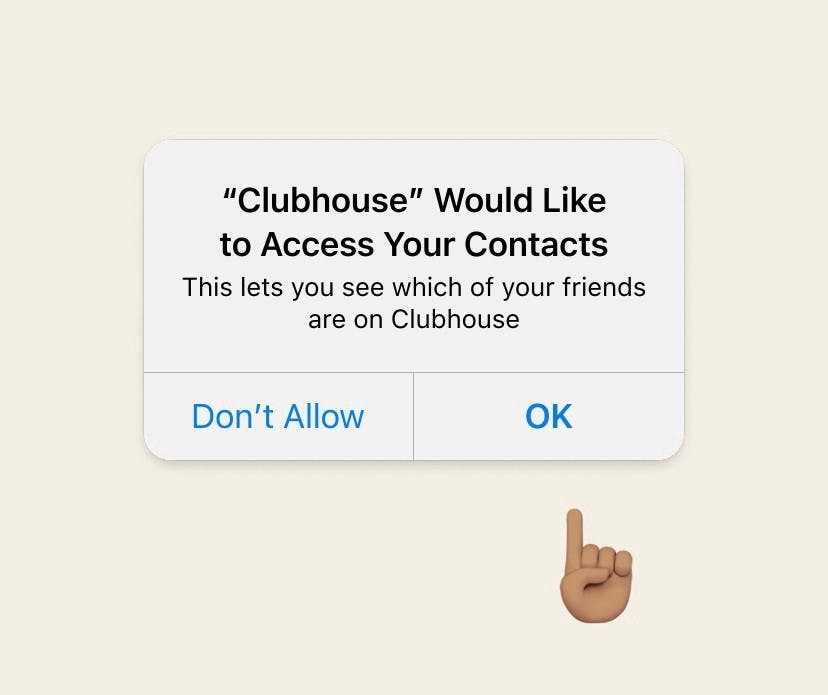

One also shouldn’t have to share “his” mobile phone contacts/address book containing “his friends” details in it. One individual’s “consent” shouldn’t undermine another individual’s rights. Period.

Clubhouse’s dark privacy pattern

Clubhouse’s dark privacy pattern

The single fact that clubhouse could fund a 100 millions dollars serie B investment to implement their fear-of-missing-out strategy, with no concern whatsoever for privacy, is mind blowing.

Clubhouse is new but certainly not alone in its data hungering quest, despite consent regulation and technologies. With privacy labels now available for many of the top apps in the apple store, more data is now available:

Every time you search for a video on YouTube, 42% of your personal data is sent elsewhere. This data goes on to inform the types of adverts you’ll see before and during videos, as well as being sold to brands who’ll target you on other social media platforms. YouTube isn’t the worst when it comes to selling your information on. That award goes to Instagram, which shares a staggering 79% of your data with other companies. Including everything from purchasing information, personal data, and browsing history. No wonder there’s so much promoted content on your feed. With over 1 billion monthly active users it’s worrying that Instagram is a hub for sharing such a high amount of its unknowing users’ data.

](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/2000/1*lFHURq8yR19-PnOpifT41Q.jpeg) Source: https://blog.pcloud.com/invasive-apps/

Source: https://blog.pcloud.com/invasive-apps/

Those results confirm qualitative Bietti’s analysis: “Notwithstanding literature and findings lays significant doubts on notice and consent’s adequacy as a regulatory device in the platform ecosystem.”

It’s Time for a Mindset Shift

Privacy, like digital identity, is a shared property. “Consent is social and contextual” (source: Sheldrake). We now have a few years of experience, and it’s time we address consent fatigue.

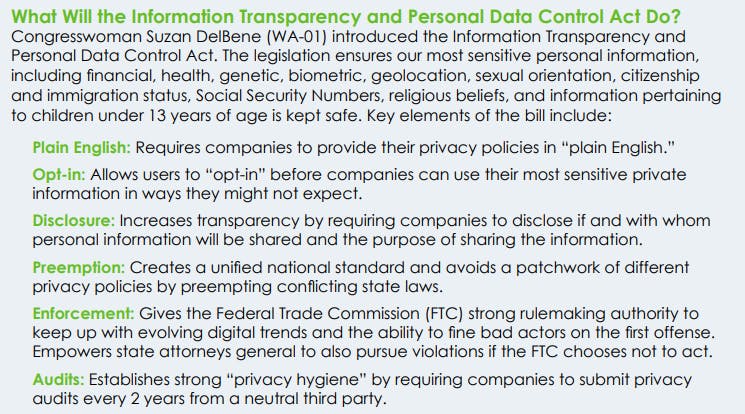

Unlike the GDPR, which gives consumers the right to “opt-out” from the sale of their personal data, NY privacy act (reintroduced in 2021) would require consumers to “opt-in” for the use of their personal data. A U.S. Consumer Data Privacy Legislation is being drafted:

Towards a national privacy law in the U.S. ?

Towards a national privacy law in the U.S. ?

The upcoming EU’s Digital Markets Act is contemplating blacklisting bad data practices and identifying digital gatekeepers (i.e. mainstream platforms), while others focus on reasonable person tests layered on top of consent (e.g. PIPEDA in Canada). To the opposite, post-Brexit UK is considering relaxing the rules “to drive growth”, says UK Digital Secretary Oliver Dowden. Digital privacy remains an eminently political matter.

The difficulty is to find the right balance, and encourage actual enforcement by companies. Data isn’t the new oil, and regulators are coming. Alongside, we technologists, as well as social scientists, should find new ways to make the much needed change happen. Digital consent is a tool, not an aim.

](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/2000/0*zoD52SxUcMWlndLX.png)